Broadcom eCos | Reversing the OS Memory Layout

In this article I’ll explain my methodology to reverse the memory layout used by eCos, and more specifically by the Broadcom variant of eCos.

Our objective is to identify:

- any vector location (interrupt vectors, exception vectors, virtual vector table, etc)

- the .text section

- the .data section

- the .bss section

- the stack location

- the heap location

While it may not be quite clear now, documenting this will be helpful in the future. It will be a time saver when reversing firmware files given that you’ll have a clear memory map, and will provide the necessary background when thinking about exploitation.

We’ll go through each specific location one by one in the next sections.

Identifying Vectors Location

By reading the eCos source code for MIPS and doing some research into dedicated vectors, I identified the following locations:

| Vector/Table | Address |

|---|---|

| Common Vector | 0x80000000 |

| Stub Entry Vector | 0x80000100 |

| Debug Vector | 0x80000200 |

| Virtual Service Routine Table | 0x80000300 |

| Virtual Vector Table | 0x80000400 |

I advise you to go through the material on exception and interrupt vectors if you want to know more about the subject. It’s not a requirement for the rest of this article though.

Identifying the BSS section

During the boot sequence, eCos clears the .bss section. This action is executed by the hal_zero_bss function. That function is defined in ./packages/hal/mips/arch/v2_0/src/vectors.S, in pure MIPS assembly.

The function is reproduced below:

##-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

## hal_zero_bss

## Zero bss. Done in assembler to be optimal rather than using memset,

## which would risk zeroing bss while using it.

FUNC_START(hal_zero_bss)

#ifdef CYGHWR_HAL_MIPS_64BIT

#define STORE_OP sd

#define BLOCK_SHIFT 6

#else

#define STORE_OP sw

#define BLOCK_SHIFT 5

#endif

la a0,__bss_start # start of bss

la a1,__bss_end # end of bss

andi a2,a0,mips_regsize-1 # is bss aligned?

bne a2,zero,1f # skip word copy

nop

# loop with 8 stores per loop

subu a3,a1,a0 # get length

srl a3,a3,BLOCK_SHIFT # get number of blocks

sll a3,a3,BLOCK_SHIFT # get length of blocks

addu a3,a0,a3 # get end addr of blocks

2: STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*0)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*1)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*2)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*3)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*4)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*5)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*6)(a0)

STORE_OP zero,(mips_regsize*7)(a0)

addu a0,a0,mips_regsize*8 # next addr

bne a3,a0,2b # to next store

nop

# If length is a multiple of block size then we

# are done and need to skip the byte loop

beq a1,a0,3f

nop

# finish 1 byte at a time

1: sb zero,0(a0) # zero memory

addiu a0,a0,1 # next addr

bne a0,a1,1b # to next store

nop

3: jr ra

nop

FUNC_END(hal_zero_bss)To us, the most important bits of information from the assembly are that the code loads the start address of .bss (__bss_start) into register $a0 and the end address of .bss (__bss_end) into register $a1.

Let’s look at actual firmwares to see what it looks like. On a Netgear firmware, we see that it starts with:

hal_zero_bss

80004854 3c 04 81 61 lui a0,0x8161

80004858 24 84 68 c8 addiu a0,a0,0x68c8

8000485c 3c 05 81 b5 lui a1,0x81b5

80004860 24 a5 25 70 addiu a1,a1,0x2570

80004864 30 86 00 03 andi a2,a0,0x3

80004868 14 c0 00 12 bne a2,zero,LAB_800048b4

8000486c 00 00 00 00 _nopSo for that firmware, we know that __bss_start is set to 0x816168c8 and __bss_end to 0x81b52570.

Another example, this time with an ASKEY firmware:

hal_zero_bss

80004854 3c 04 81 97 lui a0,0x8197

80004858 24 84 9f 48 addiu a0,a0,-0x60b8

8000485c 3c 05 81 bc lui a1,0x81bc

80004860 24 a5 89 a0 addiu a1,a1,-0x7660

80004864 30 86 00 03 andi a2,a0,0x3

80004868 14 c0 00 12 bne a2,zero,LAB_800048b4

8000486c 00 00 00 00 _nopHere, __bss_start is equal to 0x819760b8 and __bss_end is equal to 0x81bc7660.

We discovered that hal_zero_bss always starts at the same offset (0x80004854), regardless of the firmware vendor. This is due to the way eCos compilation works and the fact that hal_zero_bss is defined before eCos packages or external libraries.

Given an arbitrary firmware file, we should be able to auto-identify the start and end locations of the .bss section by seeking to that offset and matching on the instructions setting registers $a0 and $a1.

We developed the Python 3 script below to do so:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import re

import sys

import struct

offset = 0x854 # 0x80004854 - load_address 0x80004000

flirt = re.compile(b"\x3c\x04([\x00-\xFF][\x00-\xFF])\$\x84([\x00-\xFF][\x00-\xFF])\x3c\x05([\x00-\xFF][\x00-\xFF])\$\xa5([\x00-\xFF][\x00-\xFF])\x30\x86\x00\x03\x14\xc0\x00\x12")

fp = open(sys.argv[1], 'rb')

fp.seek(offset)

instruction = fp.read(24)

match = flirt.findall(instruction)

if match:

a0_upper = struct.unpack(">H", match[0][0])[0]

a0_lower = struct.unpack(">H", match[0][1])[0]

a1_upper = struct.unpack(">H", match[0][2])[0]

a1_lower = struct.unpack(">H", match[0][3])[0]

a0 = (a0_upper << 16) + a0_lower

a1 = (a1_upper << 16) + a1_lower

print("__bss_start: 0x{:0x}\n__bss_end: 0x{:0x}".format(a0, a1))

fp.close()To confirm our assumption, we ran the code on 7 other firmwares (on top of the Netgear and ASKEY ones). We successfully identified the .bss start and end address on each of them.

find firmwares -name "*out" -print -exec python3 identify_bss.py {} \;

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/epc3008/e3000-c1000r5593-150723c.out

__bss_start: 0x80789f78

__bss_end: 0x808a24b0

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/tc7200/TC7200.out

__bss_start: 0x814e3928

__bss_end: 0x819cb190

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/twg870/TWG870U-BA.out

__bss_start: 0x812b5260

__bss_end: 0x815e2da0

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/twg850/TWG850-4U-9D.out

__bss_start: 0x80b7e800

__bss_end: 0x80e24770

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/c6300bd/C6300BD_1TLAUS_V1.out

__bss_start: 0x814bf3f8

__bss_end: 0x816e0560

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/cbw383zn/CBW-383ZN-0081.out

__bss_start: 0x8173fb90

__bss_end: 0x81bda4a0

firmwares/bcm2-dumps/fast3890/FAST3890_TLC_50.out

__bss_start: 0x80db1e30

__bss_end: 0x81313190These firmware were downloaded and extracted from https://github.com/jclehner/bcm2-dumps/.

Identifying .data section

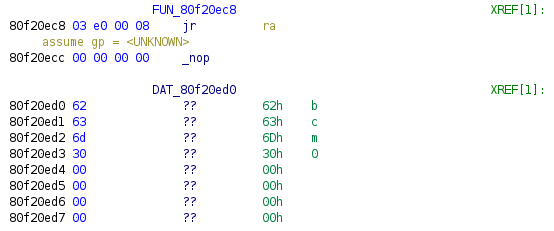

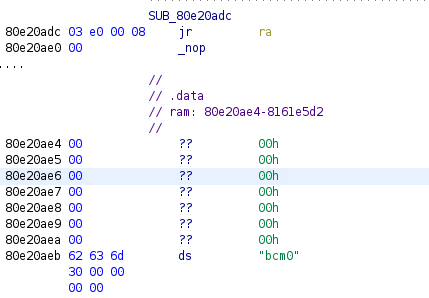

From cursory analysis of multiple eCos based Broadcom firmwares, we identified that the data section always starts with the string “bcm0”. Given that the .data section is at the end of the firmware file, it ends with a large amount of null bytes.

Here is the start of the .data section of an ASKEY firmware:

Here is the start of the .data section of a Netgear firmware, manually defined:

We can therefore identify the beginning and end of .data section with a script like the one below:

DEFAULT_LOAD_ADDRESS = 0x80004000

fp = open(sys.argv[1], 'rb')

s = fp.read()

fp.close()

data_start_offset = s.find(b"\x00\x00\x00\x00bcm0\x00\x00\x00\x00")

data_end_offet = s.find(b"\x00" * 2000)

data_start = DEFAULT_LOAD_ADDRESS + data_start_offset

data_end = DEFAULT_LOAD_ADDRESS + data_end_offset

print("__data_start: {:0x}".format(data_start))

print("__data_end: {:0x}".format(data_end))Similarly to the .bss section identification, we ran the script on a bunch of other firmware files and obtained valid results.

Identifying Stack Location

We initially identified the stack start address by executing this command from the CM shell of a live device:

CM> taskShow

TaskId TaskName Priority State

---------- -------------------------------- -------- --------

0x8195c730 Network alarm support 6 SLEEP

0x818dadd8 Network support 7 SLEEP

0x81960ef0 pthread.00000800 15 EXIT

0x81753c48 tStartup 18 SLEEP

0x87e7754c NonVol Device Async Helper 25 SLEEP

0x818d8088 Idle Thread 31 RUN

0x87e35c44 LED Controller Thread 23 SLEEP

0x87e34458 Reset/Standby Switch Thread 23 SLEEP

0x87e2fbd0 Foxconn Timer Thread 23 SLEEP

0x87e1e1cc eRouter Ping Thread 29 SLEEP

0x87e7dd1c WDOG 17 SLEEP

0x87d1b3c8 CfgVB Thread 23 SLEEPThe first task is tStartup and its dedicated stack zone starts at 0x81753c48, which is the lowest address of the list.

We obtain similar results with the command ‘stackShow’:

CM> stackShow

Stack Stack Stack

TaskId TaskName Priority State Size Used Margin

---------- -------------------------------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

0x8195c730 Network alarm support 6 SLEEP 5328 1424 3904

0x818dadd8 Network support 7 SLEEP 8192 760 7432

0x81960ef0 pthread.00000800 15 EXIT 7804 1216 6588

0x81753c48 tStartup 18 SLEEP 12288 9784 2504

0x87e7754c NonVol Device Async Helper 25 SLEEP 3072 500 2572

0x818d8088 Idle Thread 31 RUN 2048 1064 984

0x87e35c44 LED Controller Thread 23 SLEEP 4096 900 3196tStartup is always the first thread to be created on the Broadcom platform. Therefore, this thread’s stack base address will be the system’s stack base address.

The launch of tStartup is performed by calling cyg_thread_create, the assembly is provided below:

3c 07 80 fc lui a3,0x80fc

24 e7 03 34 addiu a3=>s_tStartup_80fc0334,a3,0x334 = "tStartup"

3c 08 81 74 lui t0,0x8174

25 08 7c 48 addiu t0,t0,0x7c48

24 09 30 00 li t1,0x3000

3c 10 81 75 lui s0,0x8175

26 0a 3d 70 addiu t2,s0,0x3d70

3c 0b 81 75 lui t3,0x8175

0c 34 d1 0a jal cyg_thread_create undefined cyg_thread_create()

25 6b 3c 48 _addiu t3,t3,0x3c48cyg_thread_create signature follows:

void cyg_thread_create

(

cyg_addrword_t sched_info, /* scheduling info (priority) */

cyg_thread_entry_t *entry, /* thread entry point */

cyg_addrword_t entry_data, /* entry point argument */

char *name, /* name of thread */

void *stack_base, /* pointer to stack base */

cyg_ucount32 stack_size, /* size of stack in bytes */

cyg_handle_t *handle, /* returned thread handle */

cyg_thread *thread /* space to store thread data */

)Instead of using registers $a0 to $a3 for parameters, and then the stack to store subsequent parameters, the Broadcom platform use an interesting convention which consists of putting parameters in registers $a0 to $a3, then $t3, $t1, $t2, and $t0.

Given cyg_thread_create signature, we’re interested in the value put in register $t3 which corresponds to the pointer to the base of the stack (stack_base), along with the value put in register $a3, which is a pointer to a string holding the thread’s name (“tStartup”).

We can auto-identify the stack start address of any Broadcom firmware by following these steps:

- identifying the string “tStartup” in the binary

- cross-reference that string to a location where it is loaded into register $a3

- from there, match instructions setting register $t3 value. That value is the stack start address.

Identifying Heap Location

We can obtain information about the heap by going into HeapManager menu and typing stats:

CM> cd HeapManager

CM/HeapManager> stats

BcmHeapManager basic statistics:

Initial heap size: 104528528 bytes

Free memory: 75084260 bytes

Largest block: 74433844 bytes

Low water: 74433844 bytes

Node size: 12 bytes

Nodes on free list: 17

Nodes on alloc list: 103276

Alloc fails: 0 (not enough memory)

Free fails: 0 (invalid memory pointer)

Region[0] start = 0x81b52570

Region[0] end = 0x87f01ff4 (with overhead)

BcmHeapManager: BCM_HEAP_BOUNDS_CHECK is compiled out, so these counters will report 0!

BcmHeapManager BoundsChecking stats:

Counter Value Notes

---------------- ------------ ------------------------------------------------

AllocsCorrupt 0 Memory corruptions detected during malloc/realloc

FreeCorrupt 0 Memory corruptions detected during free/realloc

BCheckCorrupt 0 Memory corruptions found during bounds check

NodeCorruptRecov 0 Corrupted nodes found during bounds check that could be recovered or fixed

NodeCorruptFatal 0 Corrupted nodes found during bounds check that could not be recovered or fixed.Memory corruptions occur when a non-seed value (0xcd) is detected in an area

that should be seeded. For free memory being allocated, this is any memory

anywhere in the buffer; for allocated memory being freed, this is the buffer

zone at the front or back of the buffer that was seeded. During a bounds

check, this is all of the above.

Node corruption includes unexpected values in the fields of the structures

that track allocated and free memory.It may not be obvious, but the heap start address (0x81b52570) is precisely the address where the .bss section ends.

What’s left is to identify where the heap ends. The initial heap size is 104528528 size, it’s close enough to 100MB (104857600 bytes) so let’s just consider the heap is 100MB.

Understanding how heap allocation works on eCos will be the subject of a dedicated article.

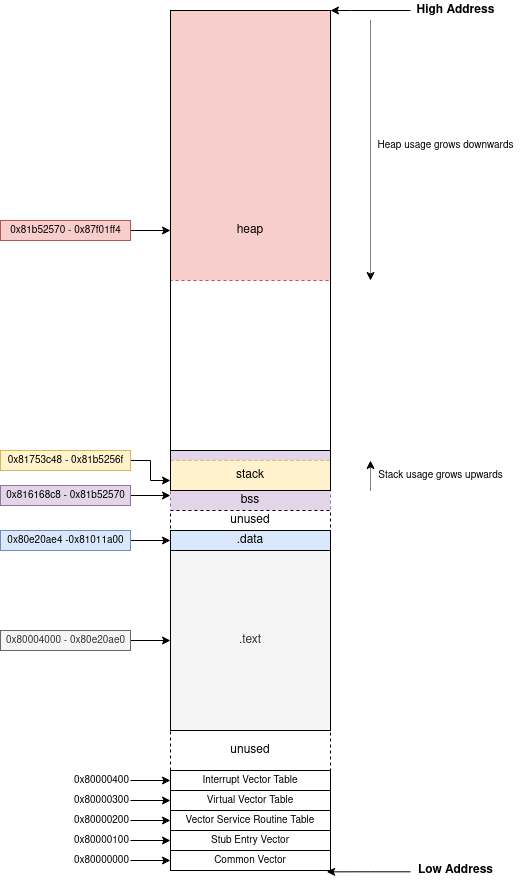

Putting Everything Together

Now that we documented the most interesting locations in the memory, let’s put everything together to have a better understanding.

The diagram below presents the whole memory used by a running device. If I’m not mistaken, there should be a dedicated stack for interrupts just below the BSS section. This region is 4096 bytes long by default. Something I still need to look into.

Thanks to everyone on the corelan slack channel for the nice debate about high addresses/low addresses locations, and whether a stack actually “grows” or not :)

I also implemented all the auto identification procedure in a Python 3 script. It’s not relying on any decompiler or disassembler library so you will get results instantly. You can get it from the dedicated repository.

python3 memory_map.py firmware.decompressed.bin

.text start: 0x80004000

.text end: 0x80e20ae0

.text length: 0xe1cae0

.data start: 0x80e20ae4

.data end: 0x81011a00

.data length: 0x1f0f1c

.bss_start: 0x816168c8

.bss_end: 0x81b52570

stack start: 0x81753c48

stack end: 0x81757c48Memory Permissions

From experience, this platform does not enforce any kind of permission flags on memory segments. The whole memory is read-write-execute.

Conclusion

In this article, we demonstrated how to reverse engineer the memory layout of the Broadcom variant of eCos.

Understanding the exact memory layout of a target is useful for exploitation and custom code injection. Now that we can identify memory regions, we know where we can write shellcode without interfering with the running system.

As always, if you have any question feel free to contact me via Twitter or email.

Tagged #ecos, #memory, #reversing.